So often I meet a new student and give them a road map of how to learn English.

In 99% of these incredibly insightful and useful first-time meetings, I mention this crucial point.

They’re not listening enough.

Why?

A language is a living, breathing, dynamic creature that you’re trying to get a hold of. When you learn a word, truly, you learn not only the definition of it, but all the collocations, i.e. the words it naturally goes with,

and all the words that it doesn’t go with,

and all the situations where you’d be expected to say it, the ones where you wouldn’t,

and implicit information about the kind of person you are for using that word.

Of course, the complexity of a word is a scale, not a binary, some are much less complex than others, which means you probably won’t be judged for using the word apple, it wouldn’t be weird to hear you use words like juice and sauce with apple (collocations), and if you asked for some apples at the store, you wouldn’t receive any weird looks.

But let’s take the word supper. Look it up, you might see that it’s an evening meal. Great, you go up to your friend and ask “What’s for supper?” And they start to laugh. How embarrassing for you. Why? Because you run the risk of sounding like their grandmother, calling the children to supper at the table in the 1950s. This is because you have learned the definition and not the supplementary contextual and societal information that allows you to use it effectively in expected situations.

How to fix it

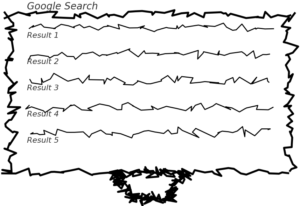

LISTEN. Really. It is the most efficient use of your time. Not only is explaining the all the associations of words difficult to do, but to give an exhaustive list of each situation where a word is or isn’t appropriate would be ridiculous. However, you DO need this information. And the best way to get it is to listen.

Listen to native speakers as much as you can, listen to people who use the language in a way that you admire, who you’d like to sound like. Each sentence they use is the intersection of all of this information, definition, context, expectation, and connotation. Each sentence is the study all of these, simultaneously, bit by bit.

Over time, you’ll gather instincts about words by who uses them and how they’re used, which will reduce the time necessary for this process. As your level improves, you’ll need less input to understand a word and its implicit information, the process builds on top of itself.

But you can’t really hack your way there, your brain has finite limits of energy, attention, and processing power.

Persistence and Interest are King(s)

I will probably repeat this a hundred times on this site: a great metaphor for learning a language is muscle-building. You can’t get “jacked” in a day, or a week, even on the greatest ‘roids. You have to go pick up these heavy things and put them down again over and over and over and over. You can find ways to do it more efficiently. You can maximize some external features, like your diet, getting enough sleep. But, as a student of mine once said, you have to do the reps.

What are the external features in this metaphor? Interest. Your brain is much more likely to retain information that you categorize as necessary or interesting. This makes seeking out input that draws you in doubly important, it is significantly more efficient. The problem is, until a later level, you’re likely not going to be able to understand any content that matches your interests or level of sophistication in thought. This is normal, and you just have to do the best you can. Focus on the voice and charisma, the vibe. As you grow, you’ll be able to appreciate topics more.

Oh, and sleep. You always need sleep.

The Mistake of Speaking

Somewhere along the way, in ESL learning, speaking started to take on the sheen of the holy grail of learning. It was modern, it was sexy, and it was much more engaging for the student.

And that’s great, many classes SHOULD be based on a speaking model.

But what speaking does is improve speaking. It helps with all those mental factors that come with speaking, confidence, relaxation, concentration, etc. It helps you practice assembling what you know.

But you can’t speak your way to a word you don’t know, you can’t speak your way to grammar that you don’t really have a grasp on. Speaking is not learning the language, it’s learning how to speak. And, importantly, it’s a way of getting responses from others, listening to them, and then actually learning!

If you speak, too much, too early, you’ll be forced into borrowing from the thing that you know, i.e. your native language. Sounds, constructions, grammar. And then these mistakes will solidify as neural connections are made.

You will have a harder time breaking the bad habits than creating good ones from scratch. I actually believe a silent period of input for 100-300 hours of listening is very very useful. Not mandatory, but useful.

What to Take from All This

Listen more, you big dummy! Not just language, but music too.